Stay Alert caffeinated gum was initially a joint project by Walter Reed Army researchers and Wrigley’s Gum. After its success with American troops, Israeli’s elite pilots and special operation forces added it to their supply arsenal in 2011. The pilots were skeptical at first, but after getting past the taste, they now carry caffeinated gum on all missions lasting more than 48 hours. Full article: Caffeinated gum keeps Israeli pilots, commandos alert

Caffeine Basics: Intro and Contents

Caffeine Basics: A User’s Manual

* Caffeine came without instructions. THIS is the missing manual.*

Welcome to my free online book about the basics of caffeine – including coffee, tea, chocolate, soda energy drinks and more. Think of this as your “user’s manual” for caffeine. It’s a complete book and separate from my blog posts. You can move through the chapters sequentially: arrows at the bottom of each Caffeine Basics Post lead you to the next entry in the book. Or you can jump around using the Table of Contents below. Blog readers may also use the site’s SEARCH button to find info in the book’s chapters and in the blog posts. NOTE: New chapters are uploaded as soon as they are completed.

Table of Contents:

The complete book includes 12 chapters in all. Chapters will be added here as they are uploaded.

1. How Caffeine Works: Flipping the Switch

Most of us treat caffeine like electricity: We don’t care to know how it works; we just flip the switch and the power turns on.

Here’s what happens when you flip the caffeine switch…

- Caffeine streams throughout the body

- Caffeine enters the brain

- Caffeine changes how you feel and think

- Caffeine produces short and long-term effects

- Caffeine acts differently in moderation than in high doses

- Caffeine makes us want more of it

What Does Caffeine Do in Your Brain?

Coffee, tea, chocolate and cola drinks are the most traditional sources of caffeine. Energy drinks and energy shots are the latest methods to boost your body with caffeine. So what happens when you perk up with one of these substances?

Coffee, tea, chocolate and cola drinks are the most traditional sources of caffeine. Energy drinks and energy shots are the latest methods to boost your body with caffeine. So what happens when you perk up with one of these substances?

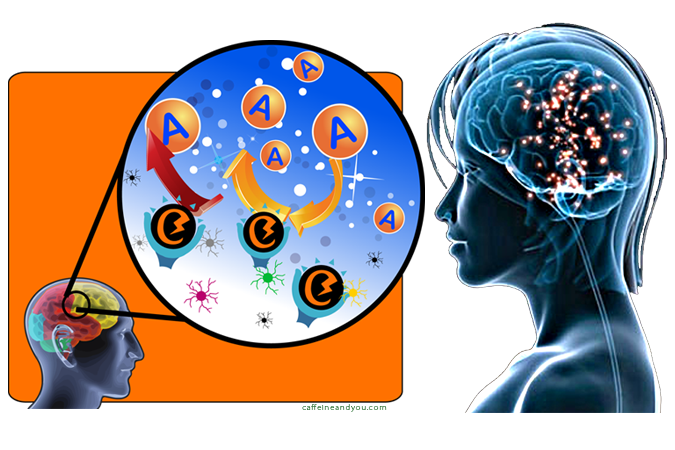

Throughout the day, brain cells create a neurotransmitter known as adenosine. Adenosine, often shortened to “ado,” is the first key to understanding how caffeine works. It’s what makes us sleepy and triggers hibernation in animals.

Adenosine gradually builds up throughout the day, giving us energy, until it reaches a saturation level. To stop its own activity, and keep us from being endlessly active, ado bonds to specific receptors – and this leads to deep, restorative sleep.

That is, of course, unless caffeine invades the brain.

Caffeine, The Great Imposter

To adenosine receptors, caffeine looks and acts remarkably like the real adenosine, so they say, “Okay, let’s bind to this guy” (not realizing he’s really caffeine). The binding of adenosine normally slows you down, but when it’s bouncing around in your brain, you’re energized and your nerve cells are speeded up. Along comes caffeine: your adenosine cells should be heading to bed, but caffeine has blocked the bedroom door.

So adenosine continues to party, and you feel alert. Meanwhile, caffeine works the room, chatting up the central nervous system with all sorts of stimulating conversation. Caffeine’s mere presence literally punches the brain’s happy button; it coaxes the brain’s pleasure center to release the ever-popular dopamine, a neurotransmitter that creates happy feelings of well being and good mood.

Neurotransmitters Join the Party

Once your neural pathways start firing on all cylinders, the “fight or flight” mode kicks in; adrenaline spikes, giving you that get-up-and-go boost. When adrenaline (also known as the hormone epinephrine) is released, the body goes into a heightened state of alert. Everything starts speeding up. Your blood pressure and heart rate rise, and your blood sugar spikes to release even more energy. You feel alert and your appetite is suppressed.

But as the caffeine in your brain subsides, so do these effects. Dopamine and adrenaline levels relax, and the real adenosine pushes past the withering caffeine to bond to its receptors.

Over time, everything returns to normal. Nerve cell activity slows down. But the brain remembers just how good that caffeine rush feels. And some experts say this feel-good state is what really leads to a caffeine habit.

But this is just a short story. Caffeine’s complete effects on the brain and body are far more intricate and subtle, as we’ll see later.

Why We Love Caffeine

People Love Caffeine, But Why?

People Love Caffeine, But Why?

Japanese pachinko machines work like regular pinball machines, except instead of playing one large steel ball at a time, they shoot off dozens of smaller balls, clattering loudly through the playing field, bouncing, racing and ricocheting into obstacles, bumpers and rabbit holes. Lights flash, whistles blow, bells ding, all the while the balls are in play. Until they gradually exit the playing space and everything stops. Kind of like your body on caffeine.

Caffeine churns through your entire system like steel balls in a pachinko machine, lighting up different responses throughout your body. Part of this has to do with the fact that adenosine doesn’t reside only in your brain. (Adenosine is the neurotransmitter responsible for energy, among other things.) Your body is full of adenosine and adenosine receptors. Caffeine has the same ability to block those receptors wherever it finds them, which can lead to some pretty interesting effects in organs other than the brain.

Adenosine, though, is only one link in the chain. Caffeine creates a domino effect among neurotransmitters, making us love it all the more.

Just as some players keep the pachinko balls in play longer than others, caffeine bounces around in some people longer than others. And as we’ll see in the coming pages, the human genome is like the Wizard of Oz: it’s the chief programmer behind long- and short-term caffeine highs.

The Caffeine Rush

When caffeine blocks adenosine reabsorption, it puts a chain reaction of neurotransmitters into effect. The caffeine-adenosine synergy amps up the levels of dopamine, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, epinephrine, serotonin, and glutamate. And collectively, these substances are responsible for how you feel, act, and think on caffeine.

For instance, caffeine sparks an adrenaline rush. When caffeine stirs up the brain’s neural activity, the pituitary gland gets confused and thinks there’s an emergency. It dispatches hormones to the adrenal glands, telling them, “Yikes, guys! Create more adrenaline!” (also known as epinephrine).

What happens when adrenaline fires off?

- Pupils dilate

- The heart beats faster

- Breathing tubes open up

- Blood flow to the skin increases

- Blood flow to the stomach slows

- The liver releases sugar for extra energy

- Blood pressure rises

It’s almost like falling in love. In fact, the caffeine rush is a lot like falling in love. In both cases, adrenaline and dopamine elevate our moods and our heartbeats, though it takes a few other neurotransmitters to spark true love. (Still, if you meet someone over coffee or a chocolate dessert, you may want to re-evaluate your relationship after the caffeine rush subsides.)

Warning: Caffeine Is Not for Everyone

Caffeine can cause bad reactions in some people, often at doses higher than 300 mg. Symptoms include restlessness, a loss of fine motor control, headaches, dizziness, insomnia, nausea, agitation, tremors, palpitations, and rapid breathing. Hand tremors, high blood pressure and anxiety are other common reactions. As we’ll see later, overuse of caffeine can also lead to serious abnormal behavior in some people, and caffeine withdrawal sparks a series of unfriendly experiences in the habitual user. Caffeine overdoses do happen, but deaths from caffeinated beverages are rare, and more likely in people with certain health conditions. Women and caffeine have a particularly roller-coaster relationship, affected by their cycle, aging hormones, pregnancy, and birth control pills. Infants and unborn children can retain caffeine in their systems for days. (More on this later.)

Caffeine is Addictive, in its own special way

Caffeine can have drawbacks, especially when mixed with alcohol and when taken in unsafe doses. It can be habit-forming, and is considered mildly addictive. It doesn’t create substance addiction the way other stimulants like nicotine and heroine do, but there’s a reason why people need their morning jolt of coffee or tea. Most people can overcome withdrawal effects of their habit, but people whose brains are already prone to addiction can face severe clinical-addiction symptoms while kicking their caffeine habit.

Bottom Line: Moderation is Okay!

The good news is most everyone agrees that caffeine in moderate consumption is safe for most people (a big change from the attitudes of the 1980s, when dubious research linked caffeine to all sorts of health problems). Since almost every person in the world consumes caffeine, this is very good news indeed. We’re not drinking ourselves into mass extinction (though some species on earth surely wish we were). And we may even be extending our lives and living healthier because of caffeine. But caffeine isn’t fully understood, and for some people, it can still be risky.

Fickle, Flighty and Evasive: Caffeine and Research Results

One thing I can say with certainty: Caffeine is quirky – fickle enough to confound its researchers. Perhaps this is just an indication of how little we know, errors in methodology, and contaminated research results. On the other hand, caffeine research results may be inconsistent because the substance itself is far more complicated than we’ve been able to pin down. Epigenetics, botany, and sociobiology are just some of the sciences pursuing the depth of caffeine’s mysteries.

One of the most difficult things about summarizing caffeine’s effects is that, depending on the circumstances, it can cause opposite responses. Scientists now believe the differences in research results may be due to genetics: some people are genetically more sensitive to caffeine than others. Studies that take these genetic differences into consideration (mostly conducted after 2010) may prove more reliable than previous ones.

Another hiccup in research results: regular vs. non-regular users. People who consume caffeine on a regular basis build up a tolerance to it, and their reactions, even when caffeine is not actively in their system, may be markedly different from people who never consume caffeine. If a study testing the effects of caffeine doesn’t control for this, the results may be inaccurate or not replicable. Even though caffeine has been tested on humans for decades, the results of early studies may lead to different conclusions when re-examined.

So don’t be surprised if you hear a wide range of claims about caffeine’s effects. Results that are consistent and replicable tend to be the most reliable. As a species, we are remarkable in our ability to question our own physiology. Even if we’re not always right at first, we keep trying, and changing our course or conclusions are an essential part of the ongoing scientific process. It took hundreds of years, and meticulous observations, for the earth to go from flat to round. With caffeine research, the next dozen years may be just as illuminating.

Coming Up…

This section on How Caffeine Works highlights only the top caffeine effects. Research is hot on the trail of more complicated results, from living longer to living healthier, as we’ll see later…

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- …

- 19

- Next Page »