Want the crème de la crème of guarana? Head to the highlands of the Maués-Açu River basin in Brazil, and seek out the Sateré-Mawé tribe – the foundation of guarana culture.

They domesticated the wild vine and cultivate it as a shrub. The Indians’ care and traditions make theirs the best quality. But they sell less than two tons per year, and like premium winemakers, they retain most of the harvest for their own consumption. Commercial companies nearby also raise guarana, but the quality doesn’t come close to that of the Sateré-Mawé tribe. (Guarana is valued as a natural source of caffeine, and a main ingredient in energy drinks.)

Raising the Children

In November, tribesmen dig up guarana saplings – known as the “children of guarana” – from the forest, and transplant them in dark, highland soils close to their villages, reachable by foot or canoe. They arrange the saplings in pairs, crossing their stems to support their growth, in rows to make an X formation, allowing the saplins room to grow and spread. It takes another two to three years to produce a harvest. If the rains are late, the flowers dry up. The more humidity, the bigger the fruit. Over decades, the tribe has developed a complex knowledge of the genetics, pollination, reproduction and nurturing of the plant, including the effects of fluctuating conditions.

The production process starts with the harvest and runs from October through March (the rainy season). To ensure the best quality, the Sateré-Mawé harvest the guarana bunches before they’re completely ripe. They pluck the seeds from the branch. Then one-by-one and by hand, the seeds are peeled quickly, while they’re most potent and before they ferment. They’re dumped into pots of water to cleanse them of their white pulp, rinsed in running water, and drained.

Preparing Guarana, the Old-Fashioned Way

The seeds are now slow roasted, stirred evenly over the fire so they don’t get puqueca (burned spots). Just as a restaurant kitchen has expert chefs for each stage of a meal, the tribes have expert piladores (seed crushers) and padeiros (bakers) who turn the product into “sticks” – loaves of guarana dough. Skilled women wash the sticks and smooth their surfaces to make them uniform. Finally, the sticks go into fumeiros, smoking areas over low fires, to be dehydrated and blackened. The tribe’s knowledge and attention to detail make their sticks the best in the region.

To drink the guarana, a woman grates the stick with a rock or more likely, the bones of a pirarucu (a large Amazon fish), into a gourd of water. The beverage, known as çapó, is drunk by all ages. It’s used as a daily boost and at ceremonial rituals. Tribesmen consider it an aphrodisiac, though this effect is unsubstantiated. The tannins in the substance are said to aid digestion, and the drink relieves headaches (probably due to the caffeine).

Not much has changed since the first white men encountered the Sateré-Mawé. Father João Felipe Betendorf wrote in 1669 that the tribes have guarana “which they praise like whites praise their gold, and which, grated with a small rock and drunk mixed with water from a gourd, provides them with so great a strength that when the Indians go hunting they do not feel hungry and in addition it makes one urinate and cures fever, headaches and cramps.” [Note: Father Betendorf’s claims have not evaluated by the FDA.]

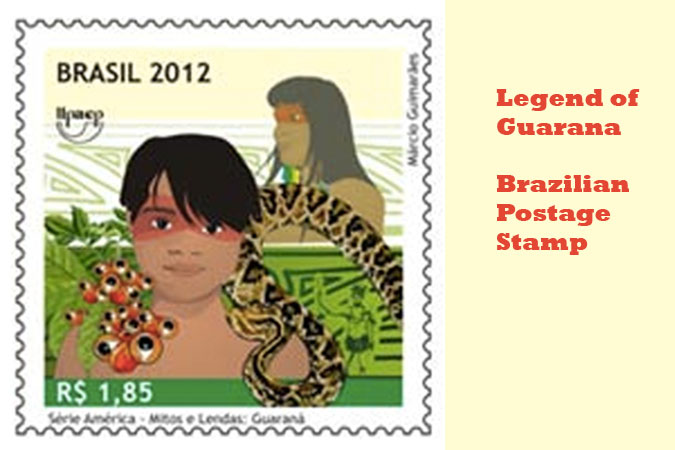

The Legend of Guarana

Both the Sateré-Mawé tribe and the plant’s forest saplings are known as the “children of guarana.” This legend explains how the plant was given to the people:

“The contrast of the colors in the split-open fruit gives them the appearance of eyeballs. Indeed, the origin myth behind guarana’s domestication is attributed to the Sateré-Maué Indians of Brazil, the first consumers of the guarana beverage, who tell of a malevolent god who lures into the jungle and kills a beloved village child out of jealousy. The village finds the dead child lying in the forest, and a benevolent god consoles them in their grief with a gift in the form of guarana. The good god plucks out the left eye of the child and plants it in the forest, where it becomes the wild variety of guarana. The right eye is planted in the village garden, where it sprouts and produces fruits resembling the eye of the child, forever after a pleasant reminder of their forever but lost child.” – H.T. Beck, The Cultural History of Plants

As with all legends, variations are plentiful. In one version, the child’s mother is a strong and courageous Indian girl who lives in the forest. Her two lazy brothers are dependent on her and prevent her from marrying, lest they must fend for themselves. The girl becomes pregnant, and gives birth to a boy with intensely beautiful eyes. But the selfish brothers kill the child. Crying and screaming, the girl throws herself over the boy’s body, and to preserve his eyes, she chews the leaves of a magical forest plant and washes the eyes with this mixture of her saliva and plant juices. She plants the eyes in the forest earth, and says “My son, you will be the greatest natural force. You will restore energy to the weak and free them from disease.” And from those eyes grew guarana.

For more on guarana, check out the Guarana Profile in Caffeine Basics.

Visit this site for images of the Sateré-Mawé tribe. and detailed descriptions of the Children of Guarana and how the tribe prepares and consumes guarana.