The young man was partying, having a good time with friends. It was a normal weekend, and for kicks, he tried something new. He chugged down some white powder, not much – a couple of teaspoons – with a can of Red Bull. Before the night was over, he’d be dead.

In 2010, Michael Lee Bedford, a 23-year old British man, died from caffeine overdose: the two teaspoons he swallowed were caffeine powder. His friend had purchased the pure caffeine over the Internet for £3.29 (about $5.50). It’s commonly sold as anhydrous caffeine powder.

The powder’s label recommended that dosage not exceed one-sixteenth of a teaspoon, smaller than the size of a pea. But Bedford never saw the label.

Bedford’s blood contained the caffeine equivalent of 70 energy drinks. And unlike caffeinated beverages, it took him but a few seconds to ingest it. That extreme amount of caffeine causes serious reactions in the body, most notably rapid heart beat and seizures. Coffee, tea, chocolate and guarana contain caffeine, but you’d have a hard time drinking or eat these naturally caffeinated products fast enough, before your body would start rejecting them.

According to an ABC News report, Bedford’s family has a strong message about the dangers of caffeine powder. “I feel like it should be banned,” his grandmother said. His aunt agreed, adding “I think there should be a warning on it saying it can kill.”

What is Anhydrous Caffeine Powder?

Caffeine is synthesized by boiling plant parts (like stems, beans, and leaves) in water. After the plant parts are removed and the water evaporates, what’s left is a dry, white, crystalline powder, known as anhydrous caffeine (anhydrous means “without water”).

The process greatly concentrates caffeine’s potency. Anhydrous caffeine is a pharmaceutical substance mixed into medicines, weight-loss and energy products, and a full range of dietary supplements. When it’s an ingredient in foods or beverages, nutrition labels list it simply as caffeine. But in its pure state, the bitter-tasting powder is a highly concentrated drug.

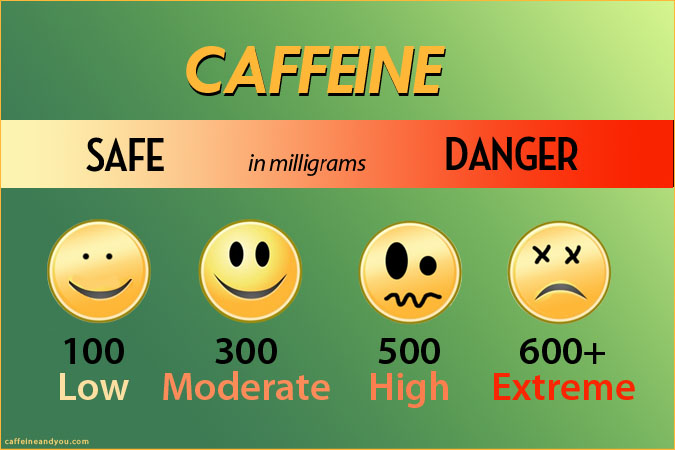

The warning label on one brand of anhydrous caffeine powder advises not to exceed 200 mg in 24 hours (which is about 1/10th of a teaspoon). A lethal dose of caffeine depends on many factors, including a person’s weight, age, and health status. But whether it’s the caffeine in powdered form or in a cup of coffee, amounts as low as 300 mg can lead to adverse reactions in some people. But you’d have to drink about 100 cups of coffee before the caffeine in it would kill you, and you’d probably be shaking too much after the first few cups to continue (not to mention the nausea and gastric reactions).

Anhydrous caffeine powder, though, is concentrated enough to produce toxic and even lethal effects within minutes, and in as little as a spoonful. Suppliers of anhydrous caffeine powder recommend using a gram scale to accurately measure dosage. The safety warnings on anhydrous caffeine products vary. Some advise that 200 mg is the limit, while others warn that 200-500 mg per day is the max. But every person is different.

For example, the anhydrous caffeine sold at BulkSupplements posts this notice:

Taking too much caffeine at once can cause elevated blood pressure, restlessness, headaches, irritability, nausea, and increased heart rate which could be very dangerous. It should also be noted that caffeine is extremely toxic in large doses. The larger the doses the more likely one is to experience negative side effects, and the more intense those negative side effects will be. In some cases large doses of caffeine beyond the recommended daily value could even be fatal. This information is not to be taken lightly.

Conclusion

The bottom-line for all caffeinated products is this: Know how much you’re taking, and use common sense.

Regardless of what the label does or does not say, consumers need to be aware that caffeine is a central nervous system stimulant, a drug that affects the body and brain. In low to moderate doses it’s generally recognized as safe for most people. But high doses of caffeine can be dangerous and, as this report shows, even lethal.

The problem with extreme caffeinated products:

Consumers don’t read labels, and in some cases the label isn’t clear about the caffeine amount contained. So high doses are easy to consume, even unintentionally.

Caffeine Basics: Table of Contents