Imagine this: You’re pushing your cart down the energy drink aisle, shopping for a can of Full Throttle Energy Drink. You almost walk right by it, before you realize, it’s there – but the label is completely different. In fact, all the energy drinks look different. They’re now called “caffeinated beverages” and you can’t find the word “energy” on any of them. Plus, they’ve got all sorts of new warnings on them:

Not recommended for children, pregnant or lactating women, persons sensitive to caffeine and sportspersons. Do not drink more than two cans per day. May not contain more than 320 mg of caffeine per liter.

You’re not dreaming. You’re also not in the U.S., or the western world. You’re in India.

International Warnings on Energy Drinks

In June 2012, India’s national health agency cracked down on “energy drinks.” Once the changes go through, energy drinks will be renamed “caffeinated beverages.” After deliberating for two years, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) took a stand on highly caffeinated drinks, stripping them of the “energy” tag, and adding safety warnings similar to ones on tobacco products. The products will also be banned from making any nutritional claims.

Energy drinks are causing a global regulatory stir. A handful of countries ban energy drinks, but most countries (including the U.S.) are still figuring out what to do. Policies are being reviewed and rewritten. The most common solution puts an upper limit on caffeine and adds warning labels to the can. In Australia, for instance, energy drinks must not contain more than 320mg/L of caffeine. Labels must disclose the amount of caffeine contained, with a statement that the product is not suitable for children, pregnant or lactating women.

The European Union stipulates that products containing more than 150 mg/liter of caffeine bear a warning of “high caffeine content” followed by the amount of caffeine contained.

France once banned Red Bull, but not because of caffeine. The safety of taurine, an added ingredient, was once considered questionable, but health-risks were never definitively proven. So today, Red Bull is sold in France and throughout the European Union.

Conclusion

What’s driving extreme caffeine consumption?

Marketing and new products. “Virgin” segments of consumers – ones that aren’t yet caffeine consumers – are prime targets. Additionally, FDA rules permit both extreme caffeine products and marketing to all age groups.

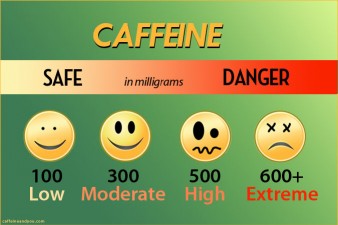

We tend to think that more is better, but that’s not the case with biphasic drugs. Caffeine is a biphasic drug; it has different effects at low doses than high ones, and adverse effects occur generally at higher doses. Most experts agree that caffeine is safe in moderate consumption for most people. Dietary supplement rules allow energy drinks, shots, and other extreme caffeinated products to push caffeine levels higher.

Here’s the problem: People can’t tell how much caffeine they’re consuming if the label doesn’t list the amount. High doses of caffeine can be risky, even for healthy individuals. Kids are especially vulnerable, including teens with heart conditions. Today’s products make caffeine fashionable to young users; and the suggestion of danger makes extreme caffeine deliciously wicked to some kids.

Caffeine overdose happens. It’s not always lethal, but it has become more frequent since extreme caffeine products arrived. Emergency rooms treat young people with reactions triggered by caffeine or large amounts of alcohol and caffeine. The untamed market for energy drinks continues to grow, especially among young, new customers – but some countries are pushing back with consumer labeling and other restrictions.

In the U.S., the FDA prefers voluntary industry restraint over federally mandated laws. Especially when a substance like caffeine is widespread and also found naturally in coffee, tea, chocolate, and guarana.

But consumer complaints and lawsuits regarding energy drink safety are mounting rapidly. At the same time, the American Beverage Association is a powerful lobbying group, whose members make everything from soft drinks, to tea, to energy drinks. Ultimately, the FDA may have a long push-pull battle with the ABA over marketing tactics and labeling, rather than restricting the amount of caffeine in products themselves.

Chapters 10 and 11 explore what doctors say about caffeine in young people, children, and adults.