Caffeine is biphasic – meaning it delivers significantly different effects when taken at low doses than at high ones.

We see this in research studies, when subjects are given small or large amounts of caffeine. But you and I can also feel the difference.

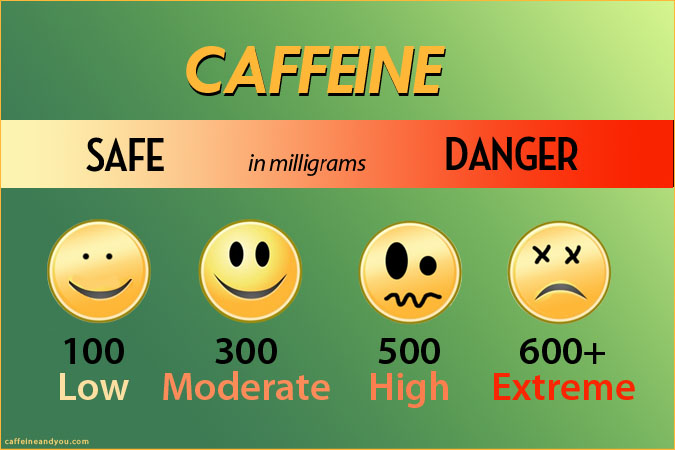

The more caffeine you ingest doesn’t mean the better the buzz. In fact, caffeine’s most popular effects – feeling good, awake, and alert – happen at low to moderate doses (100-300 mg, or one to three cups of coffee, depending on the person).

At higher doses, caffeine intoxication sets in: jitters, heart palpitations, anxiety, nausea, increased blood pressure, and such. Feeling good turns to feeling bad.

When products deliver high amounts of caffeine in concentrated doses, it’s easy to ingest too much in a short period. People with heart conditions and young people are especially vulnerable to caffeine’s adverse effects. Some energy drinks, energy shots, caffeine powder, and certain “dietary supplements” are more likely to deliver risky doses of caffeine.

Being Smart About Research Results

More and more, caffeine seems to be good for us in many ways. It’s a promising but still mysterious substance. Research results tend to conclude with the admonition “More research is clearly needed.” Or, “The mechanisms of action that account for these effects are uncertain at this time.”

Research may suggest a correlation between caffeine and an end result, but we aren’t always sure what caffeine does to get to that result.

Correlation doesn’t automatically mean causality either; there may be other factors at play, such as other ingredients in the beverage (like antioxidants), or the genetic types of the subjects. Journalists, and researchers, constantly conflate coffee with caffeine, so it’s often hard to tell which substance is really the active player.

Many of caffeine’s adverse effects reported prior to the 21st century seem to have been disproved, or not substantiated. Faulty methodology, unknowns like the influence of genetics, small sample studies, cigarette smoking, and other factors have pretty much tossed most of the scary warnings about caffeine out the door. Some prudent warnings do remain because we just don’t know enough, like the effects on newborns.

In some studies, the amount of caffeine makes a difference in results; one cup of coffee or 100 mg may be as beneficial as drinking water (i.e., no special therapeutic effect), while others require a hefty four to six cups of coffee or the caffeinated equivalent, which is enough to throttle many drinkers into the jitter zone. To make things even more confusing, caffeine in coffee may not yield the same results as caffeine in tea, sodas or energy drinks, or these other beverages may not have been tested as rigorously as coffee.

In some studies, the amount of caffeine makes a difference in results; one cup of coffee or 100 mg may be as beneficial as drinking water (i.e., no special therapeutic effect), while others require a hefty four to six cups of coffee or the caffeinated equivalent, which is enough to throttle many drinkers into the jitter zone. To make things even more confusing, caffeine in coffee may not yield the same results as caffeine in tea, sodas or energy drinks, or these other beverages may not have been tested as rigorously as coffee.

Finally, potential conflicts of interest can influence the results or their interpretation. Trade associations for coffee, sodas and energy drinks, tea, and chocolate actively fund scientific research studies. They may have no influence on the results, but it’s good to know who’s paying the bills, especially when results are conflicting or suddenly groundbreaking.

Next up: It’s all about you! How your uniqueness determines caffeine’s effects…Head over to Chapter 7